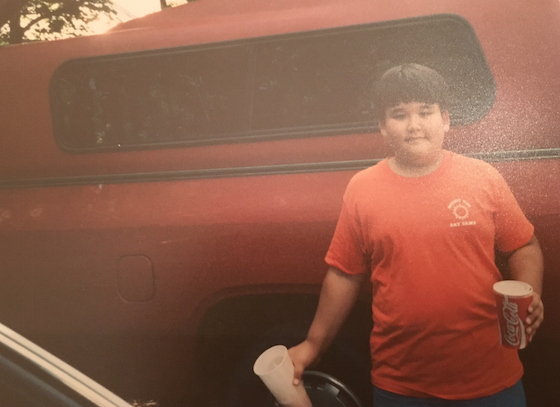

#TBT: Buttered Rolls and Bible Readings

Sundays in the early 90s were all about Jesus, Jerry O’Connell, and jamming to Toni Braxton’s “Just Another Sad Love Song.”

And since my Catholic education dictated that you weren’t supposed to eat before receiving Holy Communion at Mass, my post-church breakfasts usually consisted of buttered rolls purchased at Caruso’s Delicatessen on Centre Avenue in New Rochelle, New York. Just two for a dollar! Sometimes these rolls were accompanied by a side of fluffy, buttery scrambled eggs – because you gotta have some protein.

It became a Sunday morning ritual – walk out of Blessed Sacrament Church with my father (a Japanese Buddhist, mind you), cross the street to the deli, and walk the two blocks back to our apartment where my German-Irish-American mother (the real Catholic) was getting ready to go to work at the furniture store she co-owned three towns over in Port Chester. Working on a Sunday, the Lord’s day, was the perfect excuse for her to miss Mass. So convenient, right?

But back to the buttered rolls: I would consume these while watching old Abbot and Costello movies on the TV in my parents’ bedroom. They were also a childhood favorite of my mother’s (I was super old-school before anyone coined the term). She usually sat at her vanity table getting all made up for work, taking bites out of her own buttered roll and taking sips from her giant mug of Red Rose tea (two sugars, plenty of milk). I sat on the edge of my mother and father’s four-post, king-sized bed, careful not to get any crumbs on their floral comforter.

As I got older we changed the channel to VH1’s Top 20 Countdown because we both had an appreciation for adult contemporary music and any pop hits that didn’t involve rap or grunge. We both became mesmerized by the smoky-voiced sensibilities of a young, up-and-coming R&B songstress named Toni Braxton. Her debut single, “Just Another Sad Love Song” soon became my jam during the spring of ’93 while my mother, along with the rest of America, thought they had discovered the next Anita Baker – only sultrier.

Sunday Mass may have ended, but here in the Mitsuzuka household, mother and son broke bread over music videos for Annie Lennox’s “Walking on Broken Glass” and Amy Grant’s “Baby Baby” (from the album Heart in Motion, which, if you ask me, is one of the best pop albums of the 90s).

On one particular Sunday, after several years of attending Mass, listening to numerous bible readings, and watching the entire congregation consume those little wafers during Holy Communion, my very curious father (again, a Japanese Buddhist) declared that he wanted to see what “the body and blood of Christ” tasted like. Just like with any exotic dish or new food, his culinary curiosity got the best of him.

“I wanna go up and get Communion,” he told me matter-of-factly while Monsignor Richard performed the Eucharist at the altar in front of the crowd of parishioners, most of whom were families of kids I went to school with at New Rochelle Catholic Elementary.

“You can’t!” I told him in a panicked 10-year-old whisper.

“I’m so hungry,” my father whined. “I wanna see what it tastes like. I gotta have it.”

I wasn’t sure if he was kidding because his sense of humor was both odd and often inappropriate, and he usually said ridiculous things just to get a rise out of my mother and me.

“You’re not Catholic!” I said, stating the obvious.

“So?”

“Only Catholics can receive Holy Communion.”

“How long have I been coming to church with you? I earned it.”

“It’s a sin!” God, I was such a Catholic school sheep.

“I want some wine too.”

“No.”

“I’m gonna do it.”

“Papa, don’t.”

At this point I was already embarrassed by this whispered exchange. I thought someone was going to shush us. I bowed my head, afraid to look up and see some spinster parishioner giving us a death stare that screamed “This is God’s House! Show some respect!”

Thankfully, on that Sunday, my father didn’t do it. But the following Sunday was another story.

As we took our seats in a left rear pew of the church, my father said, “Today’s the day. I’m gonna get Communion.” I couldn’t convince him to restrain himself. So throughout the entire Mass, my anxious and hyper-imaginative 12-year-old mind conjured up different scenarios that could unfold when my father went up to receive Holy Communion. Maybe there were snipers on the parish payroll, waiting in the balcony, positioned next Mr. Gearhart the organ player, ready to take out imposter Catholics in the Eucharist line. (How could they detect the fakes? Maybe some kind of God-sponsored ray gun that beeped whenever a non-Catholic got too close to “the body and blood of Christ.”) Maybe Monsignor Richard would look my father in the eye, see right through him, and then snap his fingers, signaling a couple of Blessed Sacrament henchmen to come out of the shadows and take my father to a secret backroom where he’d be held for an indeterminate amount of time and forced to confess his sins and learn how to Hail Mary his heart out. Or perhaps the blessed wafer would instantly burn his non-Catholic tongue upon contact and send him into convulsions on the floor of the church while parishioners looked on, tsk-tsking: “We got another one.”

After a few somber numbers from the choir, a reading from a few bible passages, and one tedious homily, the moment of judgment soon arrived. As churchgoers began to get up from their kneeled positions, I did the same and got in line for Communion. I was relieved to see that my father stayed behind. Maybe he was all talk and had no intention to make an embarrassing trip to the altar. I let out a silent “Whew.” Things would be fine.

However, when I returned to my seat, my father got up and joined the last remaining parishioners in line. I froze. As he inched closer to Monsignor Richard, I looked around to see if anyone else noticed him. No snipers were poised up in the balcony. No henchmen were stepping out of the shadows behind the altar. All was okay when my father received the small circular wafer, slipped it into his mouth, and made a half-assed attempt at the sign of the cross with one hand when he turned around and headed back to his seat. I looked at him and shook my head, trying to silently communicate my utter disappointment. But he didn’t care. He glanced at me, raising his eyebrows and giving me one of his goofy smiles. The sonofabitch was proud of himself.

“Ah,” he uttered, snapping his fingers.

“What?” I asked.

“I forgot to get a sip of the wine.”

When we got home with fresh rolls from Caruso’s wrapped in a brown paper bag, I told my mother about what happened at Mass. She was just as disgusted as me. “Give me strength,” she muttered while sitting at her vanity table, putting on foundation. This was one of her trademark responses to any frustrating or stressful situation. It was also a phrase I used to mimic when I was seven or eight. I usually did it for an audience of aunts and uncles in order to up my Cute Quotient.

Years later, however, my mother would have a good laugh while recounting the story of my father’s “sinful” experience at Holy Communion to friends and relatives.

The rest of our Sunday morning carried on as usual. We buttered our rolls for breakfast, and I plopped myself in front of the TV. Like my mother, I usually layered on the butter so that there was an adequate bread-to-butter ratio. Once our routine of watching Abbot and Costello or music videos was complete, the rest of my Sunday viewing itinerary included various syndicated programming like Out of This World, a sitcom about a half-human, half-alien teenage girl who could freeze time by touching the tips of her index fingers together, and The New Lassie, a wholesome revival of the classic black-and-white series from the 50s that was too sentimental and corny even for my young tastes.

My favorite show from this kid-friendly lineup was My Secret Identity, a Canadian sci-fi-adventure comedy starring an adolescent Jerry O’Connell of Stand By Me and Piranha 3D fame. He played a teen named Andrew who gets zapped by a laser and develops superhuman powers like flying, running really fast, and incredible strength. For a good three-year period I was infatuated with Andrew/Jerry. I wanted to have superpowers like him. I wanted to be friends with him and hang out after school. I wanted to him to rescue me from sticky situations, whether it involved black-market smugglers or the dangers of teen drinking at a house party.

Once my mom left for work, I continued to sit in front of the TV for a good chunk of time. Sometimes I tried fidgeting with the set in my parents’ bedroom, not for the porny cable channels, but to see if I could get a clear picture of a local channel from Connecticut that played afternoon horror movies from the 70s and 80s. Slasher flicks like The Prowler and The Final Terror were my entertainment du jour, which later inspired me to write short stories with similar set-ups. If I couldn’t find anything on the tube, I took to my five-subject spiral notebook and wrote short stories about teens getting butchered at a sleepaway camp (Camp Nightmare, my Friday the 13th ripoff), teens getting slashed in their dreams (Frightmare, inspired by Nightmare on Elm Street), or teens getting stalked by a killer named Fred Michaels on Halloween (you figure that one out). Once in a while I would also try to mimic natural disaster epics (I was also a fan of flicks like Earthquake and The Towering Inferno) or write an occasional dramatic tale with a hint of international intrigue featuring “mysteriously handsome” characters with names like Alistair Kensington or Jonathan Weathersby.

During this time, on most Sundays, my father could be found doing a post-church round of eighteen holes at Pelham Bay Golf Course. If he didn’t come in time for lunch, my hungry ass would help myself to some Cup O’Noodles, those Styrofoam containers filled with dried starchy goodness and a “flavor packet” which was basically yellow sodium dust that either tasted like chicken or shrimp. Other times I would wait it out until he came home and cooked up a meal that included fresh buckwheat noodles, stir-fry meat, or a mound of steaming white rice with a dollop of soy sauce and a raw egg dropped in the middle.

Or if there were any leftover rolls from Caruso’s, I’d help myself to another buttered serving without hesitation. If they were getting stale, just throw them in the microwave for a few seconds, and voila, ready to eat.

This was just one example of the less-than-stellar nutritional education I received while growing up. It wasn’t as if we were poor and could only afford these fat-smeared loaves of bread as a meal. This wasn’t some Dickensian childhood full of struggle and strife. My mother, a native New Yorker, has waxed nostalgic on how she used to eat buttered rolls when she was young and growing up near the projects of Mount Vernon. My father, an immigrant who moved to the States from Japan in the late 70s, grew up with a starch-heavy diet in his rural hometown. So it appears that history has repeated itself, certain food habits from different parts of the world being passed down from one generation to the next. In no way do I blame my parents for the tastes I developed during my formative years. I was unconditionally loved, had that proverbial roof over my head, and was able to receive a private school education from the ages of 4 to 18. It just so happens that my eating habits and cravings as an adult were informed by what was fed to me so many years ago.

And oh how many eating habits and cravings there are...

*This has been another excerpt from How To NOT Stay Skinny.

@TheFirstEcho

Comments